Setaria, The Cereal Dog Killer

There's a dog killer lurking in your neighborhood: a common weed called foxtail. The many variants of the foxtail are not native to North America (with one exception), and many pet owners would gladly prescribe a Dantean punishment for the European immigrants—the Spanish in California where I live—who introduced the damned things to the New World. Native or not, chances are you see it every day during spring, summer, and fall and never think twice about it. But it's out there, and if you don't take appropriate precautions, it can kill your dog—or, at the very least, kill your veterinary budget. Here's a story of one dog that came off second best in an encounter with the foxtail—but he lived. Others have not been so lucky.

In April of 2004, my German Shepherd Dog, Oka, a healthy, 4-year-old German-bred dog out of the 2000 Weltsieger, had a brief bout of coughing. X-rays showed some lung inflammation, but a course of antibiotics seemed to clear it and we thought no more about it. Then, one Saturday in early August, quite suddenly, he became increasingly lethargic and anorexic, and by Monday he was quite ill and spent part of each following day of the week at the vet as he went from bad to worse. We had noted some corneal ulceration the previous Friday, then he developed a hard mass on his side, with some signs of lung infection, then a high fever (107 degrees), then a seroma (a swelling full of serum caused by the protein imbalance of a severe inflammation) on his left side and at the base of his sternum, and finally, the following weekend, a stiff neck and apparent loss of vision. He'd already tested negative for any fungal infections (one of the few diseases that would explain the involvement of his eyes and lungs) and his blood work, except for an elevated white cell count, was normal. So we were really worried.

That Monday (a little over a week after his symptoms first manifested), during his workup, the vet found a soft spot high on his flank where the hard mass had been, and a needle probe brought up pus. Even though it was perilously close to his spine, we decided to go in immediately, with the understanding that if it was too close to the spine or had involved any of the bony processes that she would close up and refer me immediately to a surgeon in Santa Cruz, about 45 minutes down the road.

Fortunately, Oka's spine was not involved, but what she found was pretty horrifying: an abscess that extended from his right shoulder to his left hip, crossing over his spine about midway down his body. A German Shepherd Dog's fur is very thick, and their skin fairly loose, which had hidden the progress of the infection that apparently started getting serious last weekend when we found the hard mass. She didn't find any foreign body but cleaned it out and flushed it thoroughly with Ringer's Lactate.

And here's a close-up of the wound. The bits of plastic sticking out are drains—we had to flush them out twice a day with a dilute Betadyne solution to keep the wound healing cleanly.

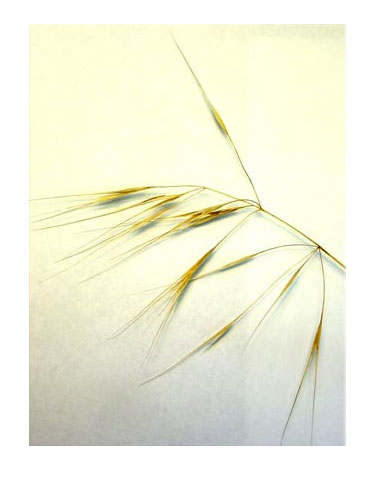

So what caused it? We don't know for sure, but we suspect the Cereal Dog Killer, setaria sp., AKA foxtail.

This is the West Coast variant of the foxtail weed, which also happens to be the most dangerous. Foxtails awns (the seed package) are designed to work their way into the ground under the impetus of the slightest breeze, and will easily do the same to flesh under the urging of the animal's slightest movement. Their points are incredibly sharp, and the spines are covered with microscopic barbs that point backwards so that they only move one way: deeper, impelled by every slight muscular twitch or even mere breathing. Oka's episode of coughing back in April may have been the result of inhaling a foxtail, which then worked his way out of his lung, through the pleural membrane, and into his subcutaneous layer. Mind you, a foxtail doesn't have to be fully inhaled to cause this kind of damage: they often enter a dog's body from between its toes, in its eyes or ears, through its nasal cavity, or even, in thick-coated dogs, through the skin.

It could have been better and could have been worse. If it hadn't been for the unrelated corneal ulceration, which suggested mycosis, we might have zeroed in on the hard mass sooner and discovered the abscess before it got so big. As it was, the bill came to over $3500. On the other hand, it could have taken a slightly different course, into Oka's abdominal cavity, with resulting peritonitis or major organ damage (a neighbor lost a cat to a foxtail that punctured her pancreas), or even into his heart. And the bacterium involved in his case, hemolytic staphylococcus, responds well to a common, inexpensive antibiotic. Furthermore, the abscess didn't damage any muscle tissue.

So, if you live in an area where foxtails are common, take this lesson to heart: they are deadly dangerous, especially on the West Coast. If your dog goes places where foxtails are common, inspect the animal carefully and frequently; you can't do much to avoid inhalation or ingestion (a favored lodging place in the latter case is the tonsil vaults), but you can stop the other ways in which a foxtail can burrow into the dog's skin and wreak havoc with its health and your budget. Best, if you can, to keep the dog away from areas with lots of foxtails, but if not, the price of your dog's health is eternal vigilance!

Ask Cindy.