Balance Problems With the American Show German Shepherd

Ed's Note: I do not often publish articles on my web site that have been written by other people, but I asked Jean Mueller permission to print this article. It addresses the structural problem with the AMERICAN GERMAN SHEPHERD. I wrote an article titled German Bloodline Dogs vs. American Bloodline Dogs. In it, I address the fact that American Shepherds have lost their temperament, drive, and working ability as a result of American Show Breeders searching for extreme angulation.

Jean's article addresses the basic conceptual mistake that American AKC Show breeders make in how they interpret what a German Shepherd Dog should look like. They are so far off the mark that they have virtually destroyed the functionality of their bloodlines.

In my opinion it is foolish, stupid, and wrong to breed an animal whose sole purpose is to enter conformation shows and run in a circle. I will guarantee you that Max Von Stephanitz never had the American German Shepherd in mind when he wrote his standards for the breed in the early 1900s.

I would like to share some ideas found through researching the American German Shepherd (GSD) as a herding breed dog. How the overall balance and structure is affected by exaggerated angles in this breed.

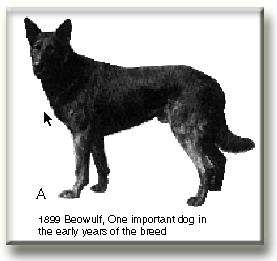

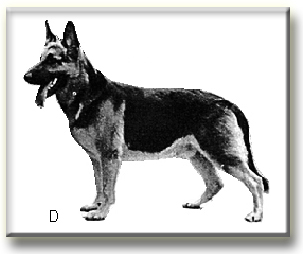

This breed originated as a herding dog. Herding dogs are trotting dogs that must have great endurance, strength and agility. In 1899 the first registry was created for GSDs called the SV (Verein fur Deutsche Schaferhunde), a society devoted to the development of the German Shepherd in Germany. Von Stephanitz as president favored dogs from Thuringia and Frankonia. These dogs were generally coarse coated, small and stocky with the prized qualities of erect ears and wolf-gray color. (See photo below)

Keeping in mind the GSD's original structure and purpose my premise is this:

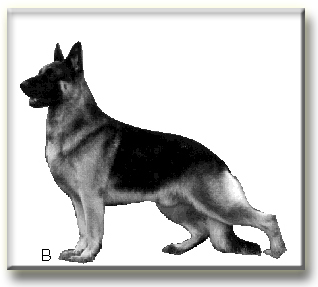

Breeding a dog solely for its flying trot has left the American German Shepherd (GSD) wobbly and easily taken off balance. This breed features an attractive fault which pleases the 'fancy' but is, in fact, a detriment to its original function. The main point of concern is agility and balance in the structure of these dogs. Out of the herding group the GSD stands apart with an exaggerated top line and extremely long stride.

Beauty or extremes often win in dog shows. If the stride is suppose to be long, then of course, the longer the better. If the stride should be long then breeders will find a way to develop longer striding dogs. Selection for aesthetics and extremes has made the American GSD what it is today. At present these dogs are not bred to function as working dogs but to win in the show ring regardless of whether it improves the dog's original purpose or not.

There should be balanced angulation for dogs designed to be endurance trotters such as the GSD. That means the angle at the point of shoulder should be nearly equal to the angle at the stifle and the angle at the elbow should be nearly equal to that of the hock joint. One definition of "Balanced Angulation" is whatever angulation is needed for the function of the breed during locomotion.

Functional tests performed on dogs indicate that 45° lay back is undesirable for a trotting dog. (Brown, 1986) If the angle on the shoulder of the GSD remains at a extreme 45° angle as is widely believed to be correct it will also continue to affect the faulty angle of the rear.

It is not reasonable to measure the angulation of the rear leg since this position can be stretched as little or as much as desired. But there is a limit to how far the rear pasterns (from the paw to the hock joint) can be pulled in towards the ischium and kept on a vertical line. The rear pasterns shouldn't be slanted forward or backward to view these angles.

In realizing these variable distances some take their measurements of angle from structural points on the body. For instance in demonstrating top line differences between German GSDs and American GSDs, a 30° angle could be found common in both types of dog using a straight line from the high point of withers to ischium (buttocks bone). (Lanting, 1997)

But how can the angles in the rear be measured if the hock can be positioned at so many places behind the body of the dog?

Not only can the problem of defining the rear angulation be confusing, it allows for many varied perceptions.

The AKC (American Kennel Club) standards requirement can be taken by breeders many different ways. Right now it's for a maximum angulation in both front and rear.

Hindquarters

The whole assembly of the thigh, viewed from the side, is broad with upper and lower thigh well muscled, forming as nearly as possible a right angle. The upper thigh bone parallels the shoulder blade while the lower thigh bone parallels the upper arm. The metatarsus (the unitbetween the hock joint and the paw) is short, strong and tightly articulated.

Gait

A German Shepherd dog is a trotting dog, and its structure has been developed to meet the requirements of its work. General Impression The gait is outreaching, elastic, seemingly without effort, smooth and rhythmic, covering the maximum amount of ground with the minimum number of steps. At a walk it covers a great deal of ground, with long stride of both hind legs and forelegs. At a trot the dog covers still more ground with even longer stride, [my emphasis] and moves powerfully but easily, with co-ordination and balance so that the gait appears to be the steady motion of a well lubricated machine. The feet travel close to the ground on both forward reach and backward push. In order to achieve ideal movement of this kind, there must be good muscular development and ligamentation. The hindquarters deliver, through the back, a powerful forward thrust which slightly lifts the whole animal and drives the body forward. Reaching far under, and passing the imprint left by the front foot, the hind foot takes hold of the ground; then hock,then hock, stifle and upper thigh come into play and sweep back, the stroke of the hind leg finishing with the foot still close to the ground in a smooth follow-through. The over-reach of the hindquarter usually necessitates one hind foot passing outside and the other hind foot passing inside the track of the forefeet, and such action is not faulty unless the locomotion is crab wise with the dog's body sideways out of the normal straight line. [my emphasis]

Transmission

The typical smooth, flowing gait is maintained with great strength and firmness of back. The whole effort of the hindquarter is transmitted to the forequarter through the loin, back, and withers. At full trot, the back must remain firm. The forelegs should reach out close to the ground in a long stride in harmony with that of the hindquarters [my emphasis]. Faults of gait, whether from front, rear, or side, are to be considered very serious faults.

The American GSD is known for its flying trot, a trotting style altered by humans. In the GSD standard, it is suggested that side overreaching is required for exceptionally long strides, necessitating the extreme angulation not found in other dog breeds.

This excerpt taken from The GSD Today written for the American GSD fancier is a good example of the popular belief in extreme angulation. "We prefer a dog with exceptionally good rear angulation as it gives him that strong forward propulsion and powerful drive he needs to maintain a smooth, effortless gait. This type of hindquarter, besides being esthetically pleasing to the eye, is also enduring, for well angulated dogs keep their feet low to the ground, eliminating waste motion. Some people erroneously criticize a dog who has good rear angulation, blaming this feature for any galling faults. [my emphasis] In all probability the faulty dog has a poor shoulder and is not a balanced animal. If the dog had a good shoulder to accompany the good rear angulation he would be able to out move any others."

This has been the direction most American Breeders have sadly been going in for much too long now.

Some in the study of dog structure and the GSD have raised comment on the apparent concept in the American fancy of "the more angulation, the better."

As Curtis Brown points out in Dog Locomotion and Gait Analysis "We now have German Shepherds with angulation which can never be used; in the walk they are disgraceful and in the trot, the hock joint never straightens (sickle-hocked)."

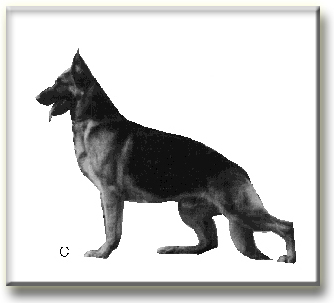

In The German Shepherd Dog A Genetic History, Dr. Malcolm B. Willis states "and hind angulation that bordered on the abnormal. Breeders proudly advertised their dogs as 'extreme at both ends movement had become the god but there was concentration upon side gait without real regard to front and hind movement (Loeb, 1988). [my emphasis] The god of movement was nothing but a graven image It is a tragedy and, alas, one sees no end to it. Pottle (1984) of Covy-Tucker Hills kennels in an interview opined that American Shepherds were structurally the best in the world! Her partner Birch (1984) felt that German imports could not compete in the show ring but she then went on to state categorically that 'a superstar (see photo above) at Covy-Tucker Hills has to have more than extreme angulation and movement to win'. The admission that extreme angulation is needed gives the lie to any claim the GSDs in the USA are going in the right direction North America has got it wrong and seems oblivious to its error in its obsession with extremes." (see photo below)

Even the American White Shepherd Association has a breed standard that emphasizes the working ability and discourages the extreme angulation seen in many colored American GSDs today. "This is a herding dog that must have the agility, freedom of movement and endurance to do the work required of it. When gaiting, the dog should move smoothly with all parts working in harmony. Overall balance, strength and firmness of movement is to be given more emphasis than a side gait showing a flying trot." [my emphasis]

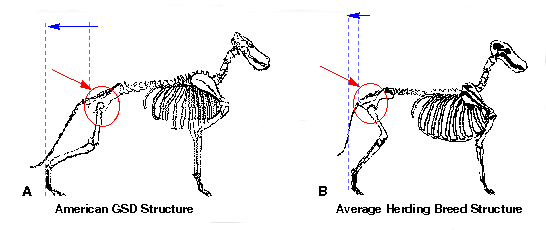

In looking at a skeleton that fits many of the current herding dogs today and that of the GSD there are two big differences. The distance of the hock from the body, and the angle of the rear leg joint including its movement in the hip socket. (See drawing below)

Taking into account that the rear leg can be posed any distance from the body, here again the rear pasterns shouldn't be slanted forward or backward but positioned as closely to the ischium as possible. (The dog should be able to physically hold this position by themselves comfortably.) This position of the leg is still so far behind the body that even though it creates an incredibly long stride at the same time it leaves the dog with a lack of balance and loss of agility. Observation of other herding breeds in motion during a specific task herding, jumping, changing direction; all require balance which is found with dogs whose feet are firmly set close to their bodies for stability.)

Compare the difference between diagram A and B and the position of the rear thighbone in the hip socket. Note how the angles are different in each. With the rear leg at this angle it does little to support the body as the foot pushes out off the ground. In my opinion this weakens the overall movement of the dog; a turn in direction or shift easily causes the dog to lose balance.

The rear legs don't give support to the back part of the dog. The rear hip joint has to support this part of the body. This leaves the joint more open to injury with any quick change in direction. The GSD now only achieves real balance when in forward motion.

References to a "full support" position in the GSD have been made in connection to balance. In some German Shepherd manuals the skeletal structure looks nothing like the GSD today. (Barwig et al, 1986) Some of these diagrams might not be accurate but it still raises questions on what should be correct for this breed. At any case what might have been true in 1950 is no longer so.

Static and kinetic balance as well as gravity should be looked at and evaluated.

American GSDs in daily routine need to be able to spin, change direction and walk without a loss of balance, which at this time they don't have. Consideration should be taken to breed a GSD that can function in all it is many facets. In trials of agility, balance, endurance and strength this breed is lacking what all other herding breeds have balance.

The origin of the GSD shows a different body type with the feet set more closely under the body.

Refer to 1950's Axel vd Deininghauserheide and others like 1953's Alert of Mi-Noah's (see photo D) (Attached at bottom of page) in which you see dogs built like other herding breeds we see today. I advocate a change in breeding and also suggest that the common hip problems in the GSD might be greatly lessened.

Let it be noted that many of the working German line GSDs today are extremely well balanced with excellent temperament. American GSD breeders need to take their blinders off to see what a REAL GSD is all about.

Bibliography

- American Kennel Club, The Complete Dog Book: New York, Howell Book House, 1997

- Barwig et al, The German Shepherd Book: Colorado, Hoflin Publishing, 1986

- Bixler-Clark, Alice. Brlarda: New Jersey: TFH Publications, Inc., 1994

- Brown, Curtis, Dog Locomotion and Gait Analysis: Colorado, Hoflin Publishing, 1986

- Collier, Marget. Border Collies: New Jersey: TFH Publications, Inc., 1995

- Lanting, Fred, The Topline of the German Shepherd Dog: Colorado, German Shepherd Quarterly, Hoflin Publishing, 1997

- Lucas, Miranda. The bouvier des flandres: New York: Howell Book House, 1990

- PettengelI, Jim. The new rottweiler: essential reading for owners, breeders: New York: Howell Book House, 1995

- Robertson, Narelle. Australian cattle dogs: New Jersey: TFH Publications, Inc., 1992

- Scott, J.p., and J.L. Fuller. Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1965

- Sloanem, Steve. Australian Kelpies: New Jersey: TFH Publications, Inc., 1991

- PaIika, Liz, 1954. Australian shepherd: champion of versatility. New York: Howell Book House, 1995

- Turnquist, Marge. The Belgian sheepdog: Virginia: Denlinger's Publishers, LTD., 1985

- Strickland, Winifred Gibson and James A. Moses. The German shepherd today: New York: Macmillan General reference, 1974

- Sundstrom, Harold W. and Sundstrom, Mary O. Collies, A Complete pet owners manual: New York: Barron's Educational Series, Inc., 1994

- Walkowicz, Chris. The bearded collie: Virginia: Denlinger's Publishers, Ltd. 1990

- Willis, Malcom B., The German Shepherd Dog, A Genetic History: New York: Howell Book House, 1991

About Jean

My husband and I started out with American line GSDs 4 years ago. I currently have three dogs. They have been shown in the breed ring as well as the obedience ring. My dogs are worked in obedience, agility, herding and fly ball. I've shown two dogs to their championships and continue to put working titles on my dogs. Due to problems with this breed health and structure wise; I began to research and talk to AKC judges, UKC judges, Breeders, and the dog community in general. I have shown other peoples dogs in breed as a way to work with as many American line GSDs as possible. And as part of my ongoing, studies I've opened my home to breeders who have puppies stay for a week or two for socialization and training. I have worked with other herding breeds as well as German line GSDs which I base my comparisons on.

Jean Mueller

Ask Cindy.